A child of mixed blood has been ritually killed by a primitive aboriginal tribe, leaving the police in the Andaman and Nicobar islands in a fix.

The Jarawa tribe has the most unique status. They are to live in a 780 square reservation with as minimal outside contact as possible.

When members of the isolated tribe venture into neighbouring villages scrounging for rice and other prized goods, like cookies, bananas or, for some reason, red garments, the police merely send them back into the ‘protected forest area’, where they are expected to survive by hunting and gathering, as they have for millenniums.

Inspector Rizwan Hassan, whose precinct includes a “buffer zone” beside the tribe’s reserve, is under clear orders: to interfere as little as possible in the traditional life of the tribe, which India prizes as the last remnant of a Paleolithic-era civilisation.

But a tribal welfare officer has registered a complaint, mentioning the name of a Jarawa man. A 5-month-old baby was dead, and witnesses came forward willingly, leaving the police, for the first time in history, confronting the prospect of arresting a Jarawa on suspicion of murder.

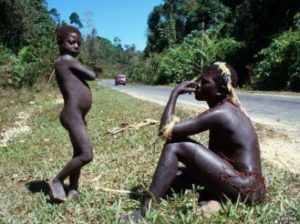

The Jarawas, who number about 400 and whom one geneticist described as “arguably the most enigmatic people on our planet”, are believed to have migrated from Africa around 50,000 years ago. They are very dark-skinned, small in stature and until 1998 lived in complete cultural isolation.

After the tribe made peace with its neighbours, India took steps to minimise contact between the Jarawas and the world that surrounds them, hoping to avoid the catastrophes that befell aboriginal people in other countries, like the US and Australia, when settlers passed on germs and alcohol.

Nevertheless, contact occurs. Outreach workers visit the tribe’s camps, and Jarawas receive treatment in isolation wards at hospitals. Poachers make illegal contact, trading food for help in harvesting crabs or fish. Such an encounter, the police believe, resulted in a baby boy with a lighter skin colour than usual being born to a Jarawa woman last spring.

M Janagi Savuriyammal, a tribal welfare officer was among the first to be alerted about the birth of a mixedrace baby. The tribe has, in the past, carried out ritual killings of infants born to widows or — much rarer — fathered by outsiders. Savuriyammal and her staff began a campaign of persuasion, presenting arguments against killing the child.

Five months later, Savuriyammal received an alarmed call from her field staff and rushed to the camp to find the baby missing and his mother crying silently.

Two witnesses told the police that the previous night they had seen a Jarawa man, Tatehane, drinking liquor with an outsider who had entered the reserve illegally. Tatehane then slipped into the mother’s hut and took the baby from her side before she awoke. The witnesses later found the baby’s body on the sand, drowned.

Savuriyammal filed a complaint with the police, but they were in unknown territory: In 200 years of fatal clashes between tribesmen and British and Indian settlers, no member of the tribe had ever been named as a suspect in a crime.

The police arrested the two non-tribal men identified in the complaint: a 25-year-old believed to have fathered the child, who was accused of rape, and a man who gave Tatehane liquor and was accused of abetting murder and interfering with aboriginal tribes. But they did not arrest Tatehane, even though he was accused of murder, instead appealing for guidance from the department of tribal welfare, according to Atul Kumar Thakur, the police superintendent.

For some time now, the authorities were struggling with the question of whether to allow the Jarawas, who are classified as a “particularly vulnerable tribal group”, more access to the world outside their reserve.

Lieutenant governor A K Singh said that one school of thought holds that “any contact of the tribe with modern civilisation has been detrimental”, while another questions how the government could deny the tribe the benefits of modern life.

How can one prosecute a person who is absolutely unaware of modern laws. “They are in a pre-civilization period. We deal with them on that basis,” says Nupur Sarkar, a policewoman. Others say if the government has forced these people into isolation, the state has no business interfering in the tribe’s traditions, even if they advocate the killing children of mixed blood.

For now, the case does not seem headed for a swift resolution.

What do you think? If you are a student, leave your comment with your name, institution and with your email address. The best answers posted over the next week will receive a gift – editor.

Why wasn’t the same yardstick: protection of primitive tribe applied in North east? Let us say in Arunachal Pradesh? Since this isolation of the Andamans has been done for over 60 years, maybe it is time to think again.

If the Government of India has denied modern development to Jarawas, the question is whether the State considers them as citizens of India or not?

How can you punish this ignorant tribal man for doing something that is ‘lawful’ in his own territory, when you have kept him ignorant of the laws of the state?

Punish the outsiders who are ‘corrupting’ the Jarawa first.

Then review the situation.

How can you keep human beings in a zoo?

The Jarawa will have to be brought towards modernity.

If the government has kept these people away from education and modern life, then it cannot apply the modern legislation to them. These people have been isolated, forced to inbreeding. So in this case, the man cannot be tried under Indian law.

First the government must end the isolation of the Jarawa.