If you wanted to know how to succeed in pop, George Michael’s career would give you a pretty good template.

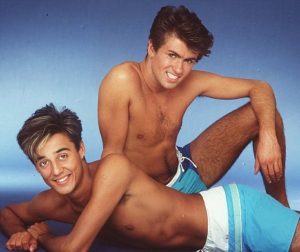

Wham! may have been considered a joke by critics who couldn’t see beyond the schoolgirls clutching Smash Hits posters to their chests, but the band were a commercial phenomenon.

Their throwaway lyrics (“Club Tropicana, drinks are free”) were full of communal, hedonistic escapism at a time when unemployment nudged three million. More importantly, the tunes had more hooks than a butchers.

Listen to Freedom: those cascading “I don’t want your, I don’t want your” vocals in the coda; or the doo-wop backing vocals after the second chorus.

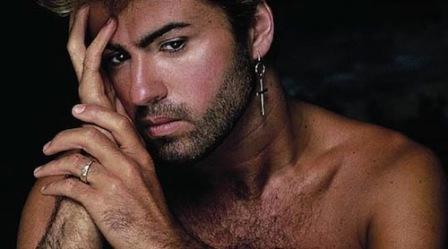

George Michael, who died on Christmas Day aged 53, had ravenously devoured pop history as a child, and you can tell from the bounding, puppy-like energy of those early records how much he enjoyed getting the chance to put his own spin on it.

The band were managed by Simon Napier-Bell, who introduced Jimmy Page to the Yardbirds and co-wrote the lyrics to Dusty Springfield’s You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me.

“I saw something in Wham! that no-one else seemed to see,” he told the NME, “which is the Hollywood thing of the two buddies, the two cowboys.

“You know, during the film, one falls in love, the other goes to a brothel, but at the end they always ride off together.”

Of course, Michael was never really this carefree, happy-go-lucky character – but he and band sidekick Andrew Ridgeley definitely played up to it in their quest for success.

“I created a man – in the image of a great friend – that the world could love if they chose to,” he once said, “someone who could realise my dreams and make me a star.

“I called him George Michael, and for almost a decade, he worked his arse off for me, and did as he was told. He was very good at his job, perhaps a little too good.”

Indeed, Wham! made George Michael a millionaire by the age of 21 – at the same time most of his contemporaries from Bushey in Hertfordshire were graduating from university.

Michael launched his solo career in 1984 with the song Careless Whisper

Beneath the surface, however, the duo were much more serious-minded than the shuttlecocks-down-shorts image suggested: They played miners benefit events with Paul Weller in the 1980s and split with Napier-Bell’s management company when they discovered a dubious South African connection.

And even though they appeared on the original 1984 Band Aid single, Michael and Ridgeley went one further than many of the other participants – donating the royalties from Last Christmas to the charity as well.

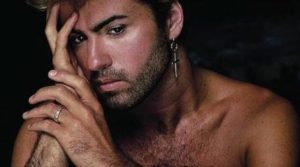

The band split once Michael had the confidence he could carry a solo career without his old school friend and, although fans were devastated, the singer had an ace up his sleeve: Faith.

Released in 1987, the album opens with a church organ playing the melody to Freedom – a funeral for a friend – before launching into a genre-spanning, attention-grabbing slew of hit singles.

The title track rides on an infectious Bo Diddley groove, before the lights dim on a dreamily romantic Father Figure, after which Michael let his libido rip on the Radio 1-baiting I Want Your Sex.

In those three songs, the star spat his bubblegum past out of the car window, and set the benchmark for any boy band member looking to establish a solo career (a teenage Robbie Williams, listening to the album in his bedroom in Stoke-on-Trent was definitely taking notes).

Faith put him on a par with other 80s superstars like Michael Jackson and Madonna. In the US, it appealed equally to both black and white audiences, selling 20 million copies, and became the first album by a white act to top Billboard’s R&B chart.

Michael was rightfully proud of the record’s musical diversity. “If you can listen to this album and not like anything on it, then you do not like pop music,” he told Rolling Stone magazine.

He went on to mount a defence of pop, in spite of his critics.

“If you listen to a Supremes record or a Beatles record, which were made in the days when pop was accepted as an art of sorts, how can you not realise that the elation of a good pop record is an art form? Somewhere along the way, pop lost all its respect. And I think I kind of stubbornly stick up for all of that.”

Still, those brickbats took their toll – 1990’s Listen Without Prejudice Vol 1 was an attempt to be taken seriously as a musician. In Freedom 90, he even expressed regret at his earlier escapades – “When you shake your ass, they notice fast / Some mistakes were built to last.”

In an attempt to shift the focus onto his music, the singer even refused to appear in his own videos: A move that only garnered him more (negative) press in the tabloids.

But his commercial instincts and pop craftsmanship were still in evidence, from the Beatles-esque harmonies of Heal The Pain to the mournful Praying For Time.

He was a trailblazer in other ways, too. Years before Prince scrawled “slave” on his face, Michael took Sony Records to court, trying to extricate himself from his contract and regain control of his career.

“There is no such thing as resignation for an artist in the music industry,” he said, after losing the case. “Effectively, you sign a piece of paper at the beginning of your career and you are expected to live with that decision, good or bad, for the rest of your professional life.”

He was also one of the first artists to realise the internet’s potential – setting up Aegean Records in 1997 specifically to sell songs online.

“I really don’t need the public’s money,” he explained. “I’d like to have something on the internet with charitable donation optional, where anyone can download my music for free.”

Ultimately, however, the company failed to make much headway.

In later years, it seemed as though Michael’s commercial instincts had abandoned him.

Certainly, the grief he suffered after the death of his partner, Anselmo Feleppa, and his mother, in the 1990s, derailed him personally and artistically for much of the decade.

Unexpectedly, his arrest on charges of public indecency in 1998 and his subsequent outing reinvigorated him. Outside, which poked fun at his arrest, was only kept off the number one slot by Cher’s mega-hit Believe; while Flawless (Go To The City) is a discofied late-career highlight.

Just weeks before his death, the star had arranged to record a new album with in-demand British producer Naughty Boy.

If the sessions, which were due to take place next year, had come to pass, it is not unreasonable to suggest that George Michael would have enjoyed a new renaissance.

[BBC]